It seems that certain eras and games can become

inexorably linked in your mind, especially when they happen at a young age.

Such is the case with a pair of classic gaming systems that began to arrive

on shelves almost exactly thirty years ago this month. The Colecovision and

Atari 5200 were released in August and November of 1982 and

subsequently began a short-lived battle against each other which constituted

one of the earliest console wars. Both super

systems promised arcade-quality gaming and largely delivered the goods. They

delivered an abundance of superb translations such as Atari’s Defender and

Galaxian competing with Coleco’s Donkey Kong and Zaxxon for gamers’

attention. Unfortunately, both consoles would succumb to the video game

crash less than two years later, becoming footnotes in gaming history,

largely forgotten except for a small number of nostalgic players. These

dedicated gamers kept the flames of the console’s alive through the decades

and with the resurgence of the classic game hobby came the advent of

homebrew games, small projects usually developed by individuals or tiny

groups that offered players the chance to play newly programmed games and

unreleased titles on these old systems. The first of these homebrew titles

started to appear a little over a decade ago, which w as a joyous

development for veteran gamers who’d filled out their collections. Recently,

we have acquired two long-standing ‘dream’ titles that have emerged from the

realm of vaporware and rumor to reality in the form of actual cartridges.

Notwithstanding some minor imperfections, these new classic releases are

quite exciting to see come to reality.

When gamers unboxed their new Colecovision consoles, one of the more

beguiling things about the package was a product catalog that featured an

extensive list of upcoming games. Many of these titles such as Rip-Cord and

Mr, Turtle would never see the light of day and would seemingly stay forever

in the ether as games that never were. This made it one of the most famous

examples of vaporware in the classic game era, with games that were forever

out of reach. At least until now, that is. A programmer named Russ Kumro

working with the hardware has spent many hours and years developing one of

these games, It’s the infamous Side Trak, an obscure Exidy arcade game that

was probably more famous for its appearance in the catalog than anything

else. Side Trak never surfaced in the realm of prototypes and this version

was impressively programmed from scratch. This is impressive achievement by

itself, and the high-quality of the release speaks to the skill and care

that’s gone into the release. The game plays a lot like the classic Atari

2600 title Dodge ‘Em but with a few differences, Your objective is to

collect all the passengers on the track, while avoiding the opposing train.

Colliding with it ends your turn and you lose a train. While Dodge ‘Em’s

levels were strictly linear, Side Track adds some unique gameplay elements.

There are some cool twists on a seemingly familiar formula that immediately

remind us of the approach found in other Coleco games such as Lady Bug and

Mouse Trap.

You can change which set of tracks your train travels by moving the tracks

before you reach the junctions, which allows you to speed out of the way or

grab a few extra passengers. The tracks twist and turn in different

directions, so you can move either east or west. The opposing train is a

dangerous foe, making it very hard to avoid at first, but you can even the

odds by memorizing its patterns and anticipating its moves. The first few

levels are fairly easy to beat, but once things move on to the later levels,

you’ll have much less room for mistakes. Adding to the challenge, passing

the start gate adds an extra train to your line, which increases the points

you get for each passenger, but also increases the danger, so you have to be

careful. Side Track takes players back on a journey through memory lane, but

its not an easy ride. Later stages become increasingly difficult and the

challenge becomes steeper the longer you play the game. Its definitely not

something you can play casually, but the high level of difficulty makes you

want to keep playing more.

The game’s production values are superb throughout with a perfect

re-creation of what a Colecovision game looked like back in the day. Its not

too elaborate or primitive and strikes a good balance. One of the cooler

aspects of the game is that Side Track looks exactly as it would have if

Coleco had programmed it. The soundtrack is a different story entirely and

features a classic rock song that’s quite appropriate and surprisingly

elaborate. We won’t ruin the surprise if you haven’t played it yet, but

Coleco sound effects maestro Daniel Beinvenu has created an excellent

soundtrack that fits the action perfectly. We also need to mention

Collectorvision’s Jean-Francois Dupuis, who produced the actual game

packaging, which looks and feels like an authentic Coleco release, with a

glossy box, excellent manual and nice cartridge that fits right in with the

classic games. We’re very happy to finally get a chance to play Side Trak

after all these years. Thanks to everyone involved in this for creating an

excellent game that brings a forgotten gem back to life with style.

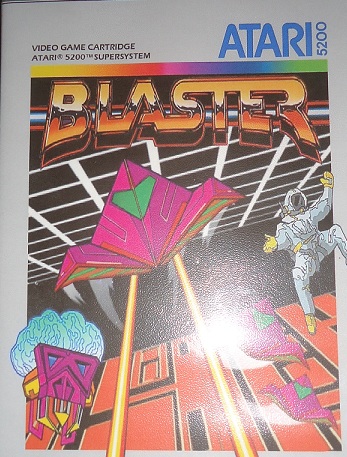

Another title with an interesting back-story is

Blaster, which finally emerged a few years back from the prototype realm. At

first glance you might think that the game was based on the arcade game that

appeared on the Williams’ compilations from a few years back, but that would

be incorrect. There’s actually a more interesting story behind the game. Its

developers Eugene Jarvis and Larry Demar began work at Williams, programming

the legendary Robotron: 2084. After this success, they split off on their

own and formed a small development company called Vid Kidz. One of the

projects they worked on was Blaster, a visionary 3D shooter that was

originally created for the Atari home computers (800/XL/XE, etc.) and the

Atari 5200. It was then converted into an arcade game, which saw limited

release since it came out during the crash. The home versions were never

released and Blaster was seemingly consigned to obscurity until the

prototypes were discovered many years later.

Blaster was an unofficial follow-up to Robotron that took place in 3D space

with multiple levels and styles of play. The game begins as you fly over the

surface of an alien planet avoiding and shooting an army of robots with you

in their sights. When they hit the ship you’re flying, you lose a little bit

of energy which can be replenished by grabbing one of the ‘E’ icons that

come out. You earn extra points by flying through the gates and can speed up

or slow down in order to fight them. After awhile on this level, you warp to

the next stage, where you’re flying through a tunnel where astronauts are

falling, collecting them earns you bonus points as well and once you’ve gone

through this, you move onto the Asteroid field. In this stage, you objective

is to shoot them and collect the astronauts while avoiding the UFO’s that

attack you. The fourth stage returns you to the planet’s surface, but now

you have additional enemies to contend with. Once you defeat these

opponents, Blaster cycles back to the first stage. As is the case with many

classic games, the action begins anew, with faster, harder enemies providing

a stiffer challenge. It isn’t that complicated – you simply aim and shoot,

but the different objectives in each stage keeps it from becoming

monotonous. It also controls smoothly, with the 5200’s analog joystick

perfectly suited to its 3D, flying mechanics. The gameplay is solid and

entertaining, perfectly in-line with the frenetic pace of games like

Defender and Robotron. The most impressive aspect of Blaster isn’t the

gameplay, but its forward-looking approach to its presentation and visuals.

Playing the game and comparing it against the arcade edition shows that the

gap, while noticeable, isn’t nearly as noticeable as it was in other titles

of its era.

Blaster was an unofficial follow-up to Robotron that took place in 3D space

with multiple levels and styles of play. The game begins as you fly over the

surface of an alien planet avoiding and shooting an army of robots with you

in their sights. When they hit the ship you’re flying, you lose a little bit

of energy which can be replenished by grabbing one of the ‘E’ icons that

come out. You earn extra points by flying through the gates and can speed up

or slow down in order to fight them. After awhile on this level, you warp to

the next stage, where you’re flying through a tunnel where astronauts are

falling, collecting them earns you bonus points as well and once you’ve gone

through this, you move onto the Asteroid field. In this stage, you objective

is to shoot them and collect the astronauts while avoiding the UFO’s that

attack you. The fourth stage returns you to the planet’s surface, but now

you have additional enemies to contend with. Once you defeat these

opponents, Blaster cycles back to the first stage. As is the case with many

classic games, the action begins anew, with faster, harder enemies providing

a stiffer challenge. It isn’t that complicated – you simply aim and shoot,

but the different objectives in each stage keeps it from becoming

monotonous. It also controls smoothly, with the 5200’s analog joystick

perfectly suited to its 3D, flying mechanics. The gameplay is solid and

entertaining, perfectly in-line with the frenetic pace of games like

Defender and Robotron. The most impressive aspect of Blaster isn’t the

gameplay, but its forward-looking approach to its presentation and visuals.

Playing the game and comparing it against the arcade edition shows that the

gap, while noticeable, isn’t nearly as noticeable as it was in other titles

of its era.

Instead of taking on the usual raster design that home systems were famous

for, Blaster used an ambitious 3D engine that rendered wireframe objects

that scaled and moved on the screen. This gives the game an appealing

vector-graphics aesthetic that’s quite impressive considering the hardware

it was programmed on had no inherent capacity for rendering. Considering the

age of the hardware, and playing it in context within its timeframe, Blaster

was definitely far ahead of its time in terms of scaling and technical

expertise. You can appreciate how advanced the system must have been after

you play the somewhat disappointing conversion of Star Wars: The Arcade Game

that appeared on the same hardware. Utilizing sprite based visuals, the game

doesn’t have the look, or match the speed of its coin-op cousin, which makes

it fall short of the mark. The speedy visuals and intense pace of Blaster,

by comparison, makes for an addictive and exciting title. While the

prototype seems mostly complete there are some rough spots in some sections

where the action seems to slow down. This is minor in comparison, and the

game is still one of the most playable and enjoyable prototypes on the 5200,

offering a fast, frenetic and addictive challenge to players lucky enough to

own a copy. It was definitely a technical triumph, but unfortunately, as in

many titles developed during that time became a victim of the great crash

and was ultimately played by far fewer gamers than it deserved to.

Playing Blaster and Side Trak after all these years, with their elaborate

back-stories in mind, points to the unexpected moments of classic flashbacks

homebrew developers give you. Not only do you get to play lost games that

were thought gone forever, you can step into a video game time machine where you

can relive a forgotten chapter of your childhood for a moment, reliving

happy times or, in this case, experiencing new ones.